The Commons [2004]

‘David Moore creates an incisive photographic survey of the physical centrepiece of British politics’.

The Commons project allowed me to pursue an archaeology of Britain’s most important debating chamber, exploring how an environment can act as a metaphor for wider issues, whilst submitting that environment to photographic scrutiny. During production of the work, I was introduced to the late curator, Pete James, who as custodian of the photographic collection at Birmingham Central Library wanted to get involved. The Library held the works of Sir Benjmain Stone, the C19th Birmingham politician and photographer. As a parliamentarian, Stone made photographs within the Palace of Westminster, of its architecture and of visitors to the space. Pete published Stone’s work in ‘ A Record of England’ in 2006. The connection was such that alongside a grant from Arts Council England, Pete funded much of the production of The Commons as well as my own publication in 2004.

I worked within the chamber, early mornings over a two year period.

My photographs and use of Hansard from the narrative of the book, and are accompanied by a fine essay from the writer and film maker, Philp Hoare, ‘Westminster Gothic: Power and perversion in the body politic’ that considers the Commons through a personal and hauntological perspective

Press

British Journal of Photography

The Independent

Photoshot

‘David Moore creates an incisive photographic survey of the physical centrepiece of British politics’.

The Commons project allowed me to pursue an archaeology of Britain’s most important debating chamber, exploring how an environment can act as a metaphor for wider issues, whilst submitting that environment to photographic scrutiny. During production of the work, I was introduced to the late curator, Pete James, who as custodian of the photographic collection at Birmingham Central Library wanted to get involved. The Library held the works of Sir Benjmain Stone, the C19th Birmingham politician and photographer. As a parliamentarian, Stone made photographs within the Palace of Westminster, of its architecture and of visitors to the space. Pete published Stone’s work in ‘ A Record of England’ in 2006. The connection was such that alongside a grant from Arts Council England, Pete funded much of the production of The Commons as well as my own publication in 2004.

I worked within the chamber, early mornings over a two year period.

My photographs and use of Hansard from the narrative of the book, and are accompanied by a fine essay from the writer and film maker, Philp Hoare, ‘Westminster Gothic: Power and perversion in the body politic’ that considers the Commons through a personal and hauntological perspective

Press

British Journal of Photography

The Independent

Photoshot

Westminster Gothic: Power and perversion in the body politic

Essay by Philip Hoare

When I was fourteen, we went on a school trip to Westminster. I don't remember too much about it, only that, as we trooped through the Commons' vast debating chamber - not quite smelling of cigar smoke for all its gentleman's club leather buffed to an improbable sheen - my friend Peter picked up one of the massive volumes which sat on the desk in front of the Speaker's Chair. He opened it at random, spat a wodge of chewed-up paper into the pages, and closed it. On the coach on the way home, we mused on what would happen when some lofty politican had cause to refer to the book on some obscure, arcane point of law, only to find Peter's mastications splattered across the text.

Maybe it was something about the institutionality of the place that encouraged our disgraceful anarchic act. We had, after all, come from a monastery school whose long corridors and ancient classrooms weren't unlike the lesser chambers of Westminster itself. As schoolboys used to subverting the system under which we daily laboured, it was logical that we should exhibit a similar reaction to the nation's democratic locus.

Like some mythic narrative of atavistic gloom, Pugin and Barry's palace looms large in our collective memory. Populated by medieval figures in stockings and tabards, processed about by archaic ritual, it stands foursquare in the heart of monumental London, flanked by the grey Portland stone of Whitehall, the authentic gothic of Westminster Abbey, and the cappuccino waters of the Thames. It is the embodiment of the establishment: an expression of democratic state, yet hemmed in by the Church of England and the residences of governance; a psychic space controlled by such leviathans of state which leaves only one escape route for any potential renegade, any parliamentary anarchist, to cast themselves off the terraces behind, and into the river, there to float downstream with the rest of the detritus, the floatsam and jetsam of history.

Crenellated, buttressed, brushed with gold as if gilded by some enormous hand, the Palace of Westminster echoes an era of imperial hubris and muscular Christianity. Surmounted by its phallic tower, housing the national soundtrack of Big Ben's chimes, this is not the romanticised, subversive gothic of the eighteenth century, all fey decoration and plaster fan vaulting: Pugin's historical antecedents may have been James Wyatt's fantastic, nightmarish Fonthill, and Horace Walpole's equally dreamlike Strawberry Hill, but anything further from that icing-sugar, foppish fantasy up the river at Teddington, where the Thames runs limpid past dropping willows, it would be hard to find. Perhaps, in the process of moving downstream, gothic was infected by imperialism - this was, after all, the same river which would inspire Conrad's dark heart - metamorphosed into a monstrous development of medieval style. Here, during the Great Stink of 1866, parliamentarians would resort to curtains soaked in disinfectant to mask the appalling smell of sewerage discarded raw into the river. Only when faced with this odorous reminder of the fecal nearness of life and death would the politicans address the problem of their constituents' ever-burgeoning waste.

And yet there is a sense of decadence to this sprawling institution of state; a spiritual, political, and creative dominance which is overwhelming in its expression: imposing, ornate, self-celebratory. Indeed, its guiding light, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-52), was himself a gothic creation, a man whose life, as Richard Davenport-Hines writes, 'was lived with a spiritual intensity and emotional extravagance which few people could have endured without breaking down. He was turbulent, fantastic, self-destructive, ill-starred and reviled…[and] cast himself back into the soaring glories of medieval Roman Catholic church-building'.1 As such, Pugin seems as extraordinary as the building he created. The son of a Frenchman 'with obscure aristocratic claims', the young Pugin had built model theatres in the family home 'at much expense, removing the attic ceiling, cutting away the roof, constructing cisterns, and adapting everything necessary to his object', as his biographer, Benjamin Ferrey would write in 1861. 'On this model stage he designed the most exquisite scenery, with fountains, tricks, traps, drop-scenes, wings, soffites, hilly scenes, flats, open flats and every magic change of which stage mechanism is capable…'2 It was as if he were rehearsing the future Palace of Westminster as a theatrical backdrop, to be viewed in two-dimensions from the river bank.

Pugin was married twice by the time he was twenty-one, took to the sea, was ship-wrecked, and thereafter habitually wore a sailor's uniform complete with jack boots. He converted to Catholicism in 1835 at a time when the Roman church was still seen as 'the sinister machine of cruel controls'. When a fellow traveller saw Pugin cross himself in a railway carriage, she shrieked 'You are a Catholic, sir; Guard, Guard, let me out - I must get into another carriage!'3 This was the subversive who was to create the architectural exemplar of a nation's values: Pugin saw gothic as nothing less than 'an answer to current social and cultural crises'.4

In October 1834 the old Palace of Westminster had been destroyed by fire, and a competition was held to decide who should be assigned its reconstruction. It was stipulated that only the gothic style was appropriate for 'a great national monument'.5 Charles Barry engaged Pugin as his assistant to prepare his entry for the competition, and won the commission. The foundations were laid in 1837, and building began in 1840. It would take another twenty years to complete, at a cost of £2 million. Although the argument about how far he was responsible for Parliament's exterior has never been conclusively settled (as if its worrisome debate were an aesthetic corollary to the political debate within), it is certain that it was Pugin who gave the building its detail, designing even its ink-pots and umbrella stands. It was Pugin who was responsible for 'the instantaneously convincing antiquity of the new place, and its glorious, intimidating magnificence as it rose over flat, marshy, low-built Westminster in the 1840s…'6

Pugin's end was decidedly gothic. Driven mad by overwork as he tried to create a medieval court for the Great Exhibition (its gigantic Crystal Palace itself a kind of see-through version of Westminster's institutional bulk, an imperial vitrine), the architect went insane in the summer of 1852, and that September, died in Bedlam. What he left behind - then unfinished - was a secular cathedral for an age of mass production; its repetitions of spires and crockets and row after row of windows which, for all their numerousness, tell nothing of what goes on inside, as if imbuing the building with the same sacred mystery as the churches from which it draws its style.

For an age moving too fast to invent its own aesthetic - or attempting to dignify its headlong progress by reference to an ancient past - gothic became the nineteenth- century style by default. By the 1870s it was suburbanised and commodified, and newspaper advertisments offered entire interiors in the Pugin taste, and John Ruskin would rail against the beast he had created even as it encroached on his south London suburb. 'Why Mr Ruskin leaves Denmark Hill' headlined the South London Press of 23 March 1872. 'Frankenstein flying from monsters of his own creation is the character Mr John Ruskin declares he now personates'. Twenty years' previously, the author of The Stones of Venice had given 'the impetus to the revival of Gothic'; now he complained 'I have had indirect influence on nearly every cheap villa-builder between this and Bromley, and there is scarcely a public-house near the Crystal Palace but sells its gin-and-bitters under pseudo-Venetian capitals…'

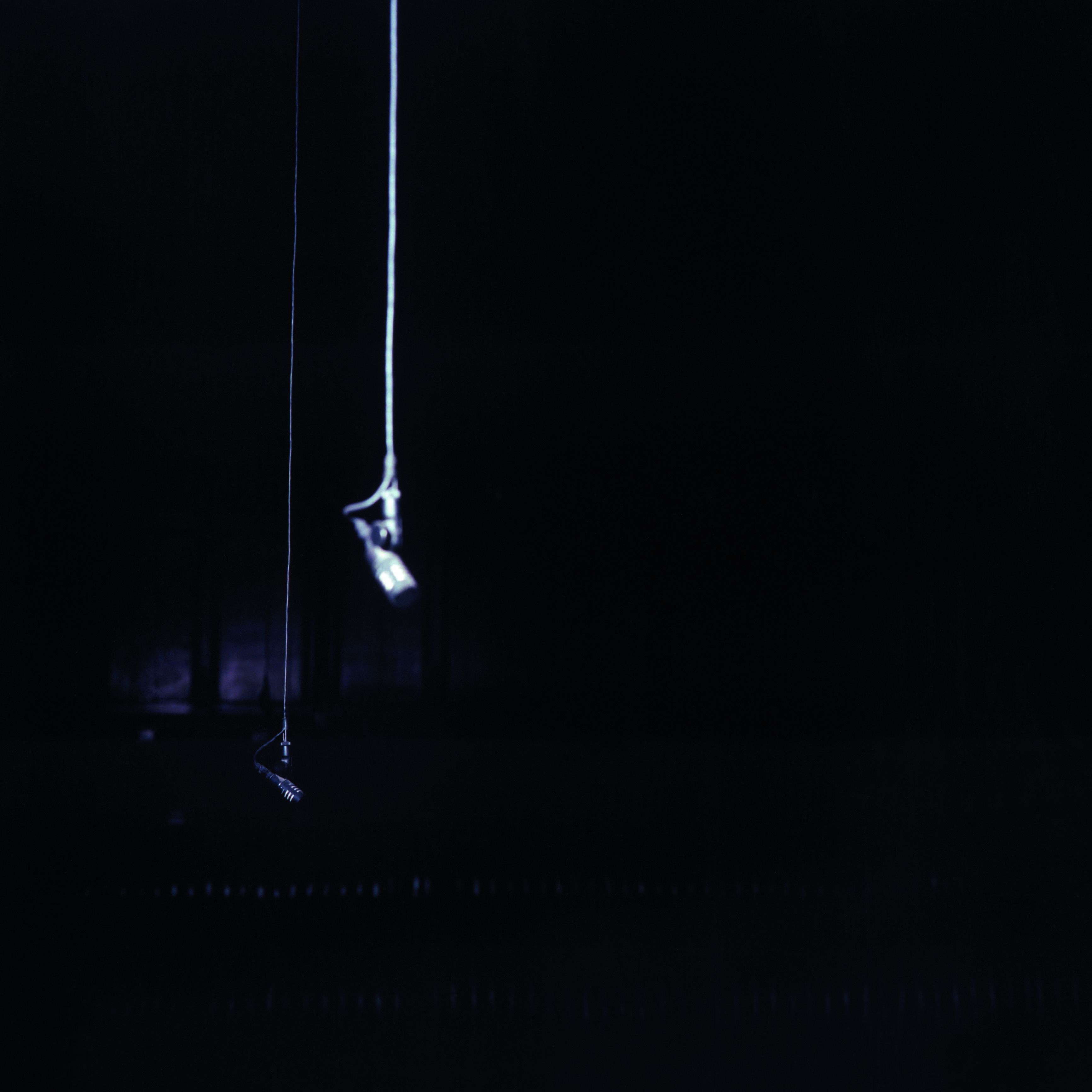

That sense of monstrousness abides in the Palace of Westminster. The German émigré W.G. Sebald would write of another gothic institution, the Palais de Justice in Brussels: 'At the most we gaze at it in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.'7 So too we see Westminster through a utopian/dystopian lens, an international emblem of all England, always seen in silhouette at one remove: from the river bank, from the train, or from the air. It seemed thus to Henry Mayhew and John Binny when they ascended over London in 1852. Republished in Humphrey Jennings' Pandaemonium, along with a Dore-like engraving of a ghostly balloon, its tethers hanging like severed threads, hovering in the penumbral, storm-clouds over the stalagmite-like skyline of the Palace of Westminster - a dark mirage out of the past or some apocalyptic future - the now industrialised city was laid before these nineteenth-century aeronauts, their journey made other by the altitude, like a map being unrolled in slow motion (a view which the contemporary visitors may obtain in a flight from the London Eye, itself a kind of Jules Verne fantasy for the millenium).

As Mayhew and Binny rose, so 'the earth seemed to sink suddenly down', leaving 'the leviathan Metropolis, with a dense canopy of smoke hanging over it, and reminding one of the fog of vapour that is often seen steaming up from fields at early morning. It was impossible to tell where the monster city began or ended, for the buildings stretched not only to the horizon on either side, but far away into the distance, where owing to the coming shades of evening and the dense fumes from the million chimneys, the town seemed to blend into the sky, so that there was no distinguishing earth from heaven'.8

So too Westminster would be transformed in the national imagination, from Turner's fiery vision and Whistler's monochrome view, the twinkling landmark of the tower of Big Ben would loom out of the metropolitan fog in the opening scenes of the Disneyfied Mary Poppins and Peter Pan and into its twentieth-century hubris, lying like some landbound Titanic on the banks of the Thames. I'm thinking of a sepia postcard lying by my desk, of the Victory Parade of 1919: a photograph of wedge-shaped First World War tanks slouching across Westminister Bridge towards Parliament. Are they celebrating the end of Armageddon? Or are they augurs of a new class revolution, an English Soviet - just as the same tanks had been deployed in Glasgow's St George's Square during the war to quell urban unrest?

I'm also reminded of the Independent MP, Noel Pemberton-Billing, a Lothario, aviator, inventor and futurist who drove round London in a self-designed car which looked more like a torpedo, and who had a ledge of skin grafted onto his cheekbone by plastic surgery so as to keep his monocle in place. In 1918 Billing alleged that the reason why the Allies were losing the war was because the German Secret Service had a Black Book containing the names of 47,000 members of the British Establishment addicted to sexual perversion. These men and women - many of them presumably habituees of Westminster - were being blackmailed by the Huns and thus the British will to win was being sapped. At the same time proposing other notions of the enemy within - not least the German Jews of Whitechapel, whom he demanded should wear cloth badges to denote the alien status of these long-established asylum-seekers - Billing's proto-fascist presence in the House of Commons was a challenge to the government; so much so that the then prime minister, Lloyd George, engineered to have the rebel MP thrown out of the House.

It was a scene unprecedented within that hallowed chamber. When the Speaker announced that Billing was to be 'suspended from the service of the House', Billing refused to move. The sitting was suspended, and officers were summoned to remove him. The incident - which has its echo in the 1980s when Michael Hestletine seized the ceremonial mace and earned his nickname of 'Tarzan' - was described with glee by the Daily Mail: 'The Speaker left the House, with several Members following him. The mace was removed from the table. Four messengers in evening dress, and wearing their gold chains of office, came in from the Lobby and closed round Mr Billing, the Serjeant -at-Arms directing operations from behind. (He did not draw his sword.) Mr Billing struggled hard, but the odds were against him. Two attendants seized a leg each, and two an arm each, and with a desperate wrench they got the member out of his corner and carried him feet first through the door, while other members laughed and cheered.'

The spectacle was redolent of Alice in Wonderland. 'The last the House saw of Mr Billing, through the swinging doors, was a scene of kicking legs and a flop on the floor of the Lobby. Fortunately the flop was on thick coco-nut mat and not on the hard tiles. In his struggles Mr Billing had grasped the shirt-front of one of his bearers and disarranged his Court dress. He also kicked another on the wrist. Thereupon they dropped him.'9 But this farce had a darker side: Lloyd George was told that Billing 'was carried out shouting "intern the Aliens"', while Billing's supporters proclaimed 'the crass stupidity of the Government in suspending Pemberton Billing has brought us nearer revolution than all previous acts combined of our subsidised marionettes. You would do well to sound public opinion, not the opinion of the camouflaged German Jews, of the monocled, eunuch-voiced inefficients who mince or waddle from Whitehall to the Clubs… That the traitors know what to expect is seen by the fact that the Statue of King Charles in Whitehall is now a machine gun emplacement' - a vision be reflected in virtual histories of SS stormtroopers marching over Westminster Bridge and Cold War fantasies of Parliament as a site for invasion from above, from Professor Quatermass to Dr Who.10

David Moore speaks of his photographs of the Commons in the context of 'the intentions of the nineteenth-century explorer photographers, who were most often in the employ of the British state to survey the colonies, for a wide range of potentiality, from land campaigns to agricultural intentions, passage, etc'.11 It is apt, then, that just along the river lies a tunnel through which transported convicts were disgorged from another institution - the verminous Millbank prison whose site is now partly occupied by Tate Britain - en route for banishment to the colonies. These wide waters were the conduit for imperial conquest, for the export of the unwanted and the import of plunder. Down in the warehouses of the docklands wharves were piled high with elephant ivory and Asian opium, an imperial trade regulated and taxed from and for the tenants of the Palace of Westminster. And so this powerhouse would abide, a sense of enclosing patronage that marched in step with the industrial age. It is no coincidence that Westminster commenced construction around the same time of the Lunacy Act, which determined that every town in the land should have a place of asylum for its mentally-ill (indeed, Pugin's contractor, the builder George Myers, was also responsible for the massive asylum at Friern Barnet). Thus, as the same time as Pugin and Barry's edifice rose over central London, multiplying in cell-like division, so the vast Victorian lunatic asylums extended the philanthropy of democracy to the insane.

My own subsequent memories of Westminster are also rooted in a certain subversion. I was at college in London during the awakening of punk: my contact with Westminster then was a series of marches routed past its then still soot-blackened, pre-steam-cleaned façade, protesting on any number of issues, from the Anti-Nazi League to the bombing of Libiya, from the miners' strike to the poll tax. All the while the Victorian complex stood as an architectural rebuttal to our democratic right to protest; an unyielding wall against which the Class War warriors could wage their civilian strife, creating, in the process, their own anti-governmental architecture: the turf mohican on place on the head of the statue of Winston Churchill; the attempt to sow fields of marijuana in the square around it; and up Whitehall their desecration of the cenotaph's empty tomb with graffitti: these auguries of inner city anarchy which would be enacted for real in downtown Baghdad.

I remember attending a book launch given on the Commons Terrace a week after 9/11: security was at its height as my fellow guests - many of them pillars of the establishment themselves - spoke of the possibilities of a terrorist attack on the Mother of Parliaments, by air or by boat; the body politic incarnate now a defensive site. That night, as I was walked its endless corridors past committee rooms and chambers, it was hard not to invest each with their own dramatic narrative, inflected with secondhand memories of Airey Neave's assassination by the IRA in 1979 - his car blown up on car park ramp - to tales of rent boys being given midnight tours of the nation's debating rooms by their uxorious sugar daddies.

Yet within this overblown version of a suburban villa - expanded ad infiniteum in its repeating arches - the machinations of Great Britain still take place, convened in endless committees and dark decisions while listless Oxbridge graduates operate as MPs assistants and catering staff cook up a Gormenghast-like storm, lacking only Peake's Swelter to swing his butcher's axe. Even now, even with its changed 'family friendly' hours, Westminster is a tradition as engrained as the Victorian pollution which still gives its façade a carbonised chiarscuro. It is still one great Pall Mall club, its terraces colour-coded between Lord and Commons, a democracy-defying diachotomy which rumour renders a venue of venal lobbying, coursed with influence and lucre through the anterior veins of its corridors and connective tissue of its cell-like chambers - the private dining rooms with their even darker panelled walls; places in which intrigue might yet foment and plots hatch over a fine burgundy.

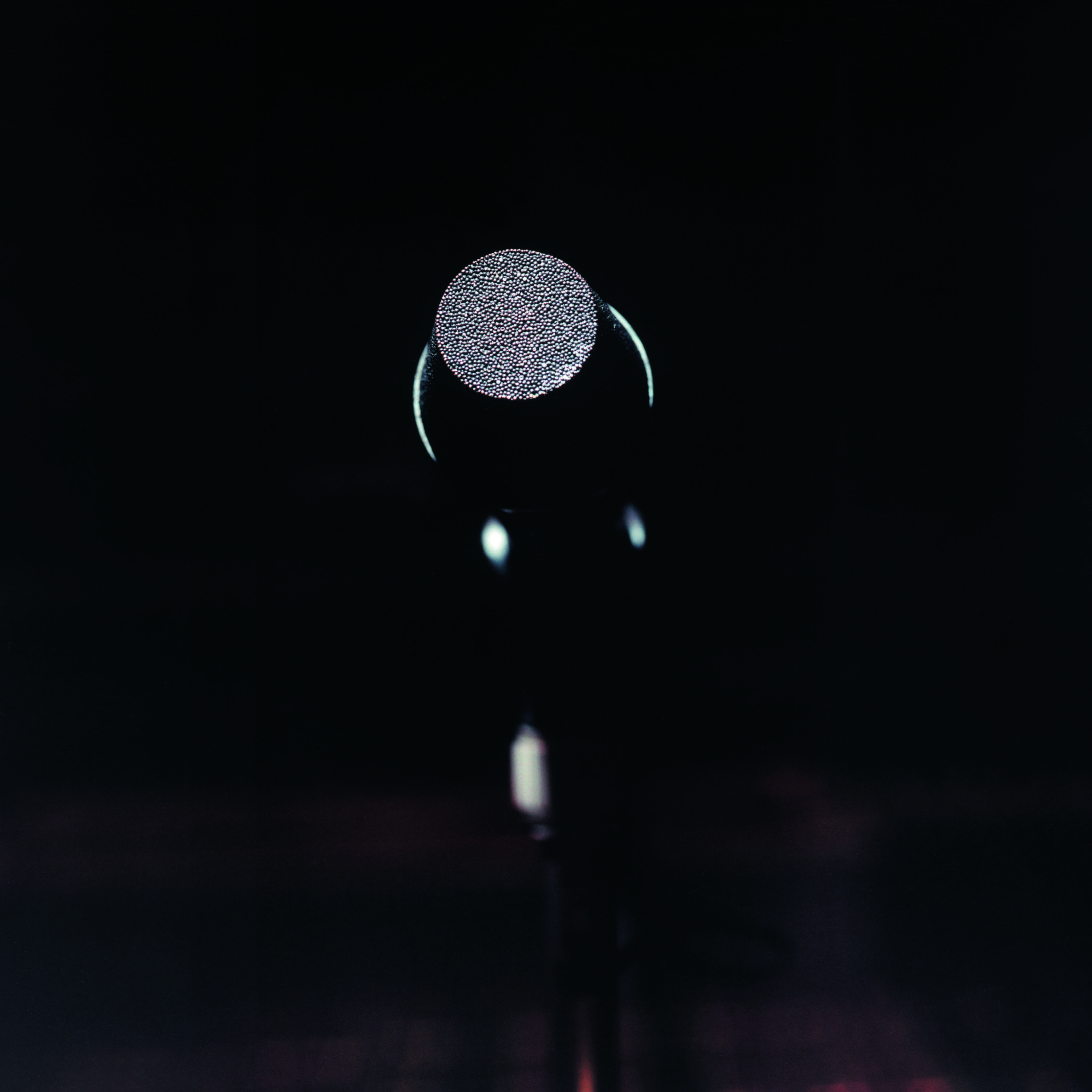

Faerie palace or demon's lair, the Commons polarises as an acute paradox: a place of the people yet ultimately exclusive. It may yet wither under the media spotlight, or even under the microscopic examination of David Moore's lens. Through its daily appearance on our TV news, the building fades into political wallpaper, its architecture a shorthand for political discourse, serious TV (one recent BBC political strand used an animated version of Westminster reconfigured as a prehistoric monster; that sense of monstrousness once more). We see it so often in bulletins and rain-soaked political vox pops and pieces-to-camera from Parliament Green that the Palace recedes into a kind of generic gothic bluescreen, as much a CGI effect as a real building. So much more powerful, then, the intrusion of David Moore's forensic images as they pathologise the textures of that interior, painted and polished, scuffed and scratched. These are charged spaces, still echoing with speeches, just as the universe still echoes with the sound of human history. The perorations of nearly two centuries hanging in the air here, just as Marconi believed he could hear the voices of the dead from his telegraph listening station - the drowning cries of long-dead seamen still reverberating in the ether.

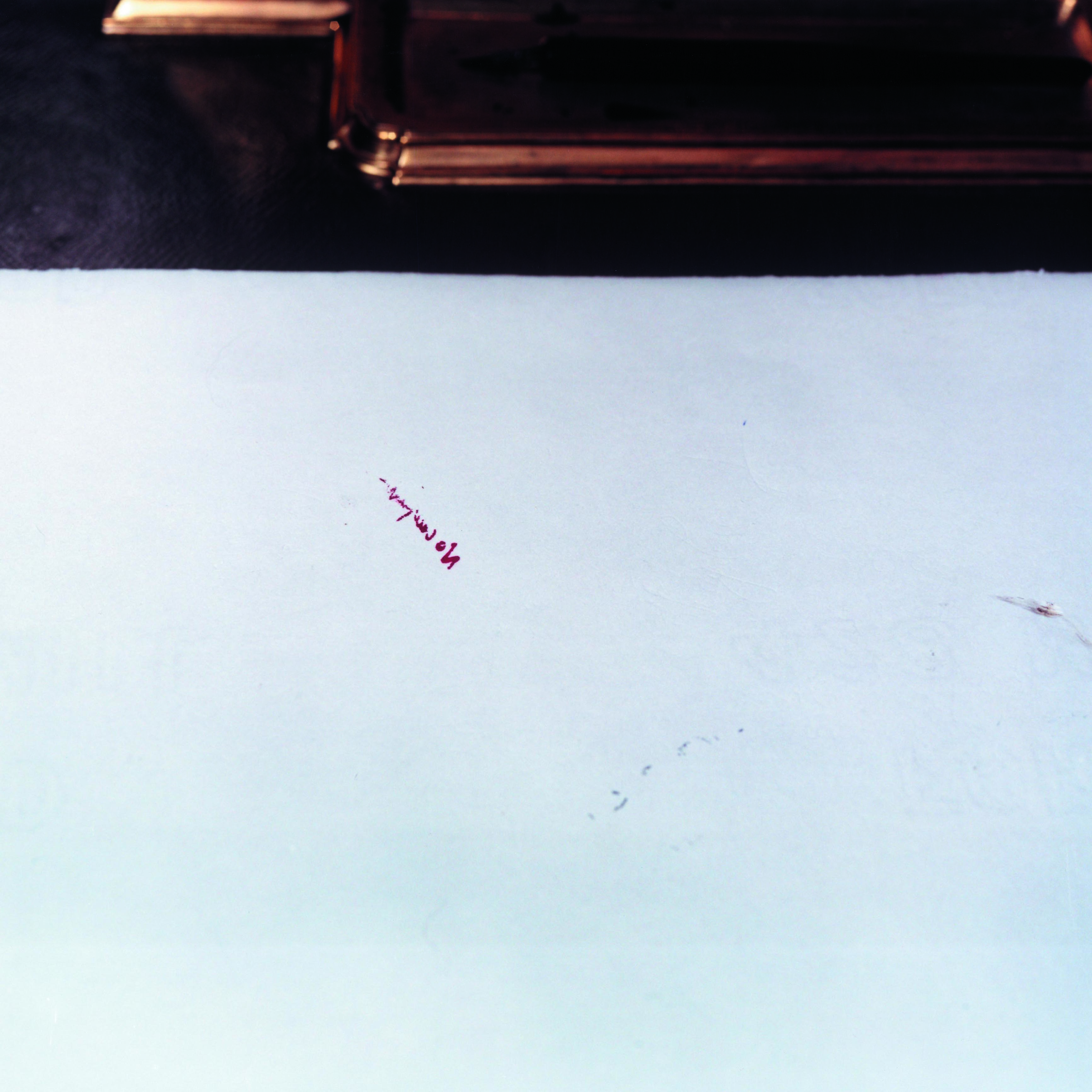

And these are the ironies which we inherit. The building may represent the will of the people, but the logo of Westminster - the medieval portcullis - speaks of defence and barred ways, antipathetic to the notion of democratic access. This is where David Moore comes in. His photographs take us into those chambers and under the seats; into the grain, as it were, examining, disinterring, preparing a visual autopsy of democracy; in his own words, 'an act of insolence in a period of absolute decadence.'12 And here, under the Prime Minister's microphone, we find a lump of chewing gum. Which is where Peter and I came in.

©Philip Hoare. 2003

Notes:

Essay by Philip Hoare

When I was fourteen, we went on a school trip to Westminster. I don't remember too much about it, only that, as we trooped through the Commons' vast debating chamber - not quite smelling of cigar smoke for all its gentleman's club leather buffed to an improbable sheen - my friend Peter picked up one of the massive volumes which sat on the desk in front of the Speaker's Chair. He opened it at random, spat a wodge of chewed-up paper into the pages, and closed it. On the coach on the way home, we mused on what would happen when some lofty politican had cause to refer to the book on some obscure, arcane point of law, only to find Peter's mastications splattered across the text.

Maybe it was something about the institutionality of the place that encouraged our disgraceful anarchic act. We had, after all, come from a monastery school whose long corridors and ancient classrooms weren't unlike the lesser chambers of Westminster itself. As schoolboys used to subverting the system under which we daily laboured, it was logical that we should exhibit a similar reaction to the nation's democratic locus.

Like some mythic narrative of atavistic gloom, Pugin and Barry's palace looms large in our collective memory. Populated by medieval figures in stockings and tabards, processed about by archaic ritual, it stands foursquare in the heart of monumental London, flanked by the grey Portland stone of Whitehall, the authentic gothic of Westminster Abbey, and the cappuccino waters of the Thames. It is the embodiment of the establishment: an expression of democratic state, yet hemmed in by the Church of England and the residences of governance; a psychic space controlled by such leviathans of state which leaves only one escape route for any potential renegade, any parliamentary anarchist, to cast themselves off the terraces behind, and into the river, there to float downstream with the rest of the detritus, the floatsam and jetsam of history.

* * *

Crenellated, buttressed, brushed with gold as if gilded by some enormous hand, the Palace of Westminster echoes an era of imperial hubris and muscular Christianity. Surmounted by its phallic tower, housing the national soundtrack of Big Ben's chimes, this is not the romanticised, subversive gothic of the eighteenth century, all fey decoration and plaster fan vaulting: Pugin's historical antecedents may have been James Wyatt's fantastic, nightmarish Fonthill, and Horace Walpole's equally dreamlike Strawberry Hill, but anything further from that icing-sugar, foppish fantasy up the river at Teddington, where the Thames runs limpid past dropping willows, it would be hard to find. Perhaps, in the process of moving downstream, gothic was infected by imperialism - this was, after all, the same river which would inspire Conrad's dark heart - metamorphosed into a monstrous development of medieval style. Here, during the Great Stink of 1866, parliamentarians would resort to curtains soaked in disinfectant to mask the appalling smell of sewerage discarded raw into the river. Only when faced with this odorous reminder of the fecal nearness of life and death would the politicans address the problem of their constituents' ever-burgeoning waste.

And yet there is a sense of decadence to this sprawling institution of state; a spiritual, political, and creative dominance which is overwhelming in its expression: imposing, ornate, self-celebratory. Indeed, its guiding light, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-52), was himself a gothic creation, a man whose life, as Richard Davenport-Hines writes, 'was lived with a spiritual intensity and emotional extravagance which few people could have endured without breaking down. He was turbulent, fantastic, self-destructive, ill-starred and reviled…[and] cast himself back into the soaring glories of medieval Roman Catholic church-building'.1 As such, Pugin seems as extraordinary as the building he created. The son of a Frenchman 'with obscure aristocratic claims', the young Pugin had built model theatres in the family home 'at much expense, removing the attic ceiling, cutting away the roof, constructing cisterns, and adapting everything necessary to his object', as his biographer, Benjamin Ferrey would write in 1861. 'On this model stage he designed the most exquisite scenery, with fountains, tricks, traps, drop-scenes, wings, soffites, hilly scenes, flats, open flats and every magic change of which stage mechanism is capable…'2 It was as if he were rehearsing the future Palace of Westminster as a theatrical backdrop, to be viewed in two-dimensions from the river bank.

Pugin was married twice by the time he was twenty-one, took to the sea, was ship-wrecked, and thereafter habitually wore a sailor's uniform complete with jack boots. He converted to Catholicism in 1835 at a time when the Roman church was still seen as 'the sinister machine of cruel controls'. When a fellow traveller saw Pugin cross himself in a railway carriage, she shrieked 'You are a Catholic, sir; Guard, Guard, let me out - I must get into another carriage!'3 This was the subversive who was to create the architectural exemplar of a nation's values: Pugin saw gothic as nothing less than 'an answer to current social and cultural crises'.4

In October 1834 the old Palace of Westminster had been destroyed by fire, and a competition was held to decide who should be assigned its reconstruction. It was stipulated that only the gothic style was appropriate for 'a great national monument'.5 Charles Barry engaged Pugin as his assistant to prepare his entry for the competition, and won the commission. The foundations were laid in 1837, and building began in 1840. It would take another twenty years to complete, at a cost of £2 million. Although the argument about how far he was responsible for Parliament's exterior has never been conclusively settled (as if its worrisome debate were an aesthetic corollary to the political debate within), it is certain that it was Pugin who gave the building its detail, designing even its ink-pots and umbrella stands. It was Pugin who was responsible for 'the instantaneously convincing antiquity of the new place, and its glorious, intimidating magnificence as it rose over flat, marshy, low-built Westminster in the 1840s…'6

Pugin's end was decidedly gothic. Driven mad by overwork as he tried to create a medieval court for the Great Exhibition (its gigantic Crystal Palace itself a kind of see-through version of Westminster's institutional bulk, an imperial vitrine), the architect went insane in the summer of 1852, and that September, died in Bedlam. What he left behind - then unfinished - was a secular cathedral for an age of mass production; its repetitions of spires and crockets and row after row of windows which, for all their numerousness, tell nothing of what goes on inside, as if imbuing the building with the same sacred mystery as the churches from which it draws its style.

For an age moving too fast to invent its own aesthetic - or attempting to dignify its headlong progress by reference to an ancient past - gothic became the nineteenth- century style by default. By the 1870s it was suburbanised and commodified, and newspaper advertisments offered entire interiors in the Pugin taste, and John Ruskin would rail against the beast he had created even as it encroached on his south London suburb. 'Why Mr Ruskin leaves Denmark Hill' headlined the South London Press of 23 March 1872. 'Frankenstein flying from monsters of his own creation is the character Mr John Ruskin declares he now personates'. Twenty years' previously, the author of The Stones of Venice had given 'the impetus to the revival of Gothic'; now he complained 'I have had indirect influence on nearly every cheap villa-builder between this and Bromley, and there is scarcely a public-house near the Crystal Palace but sells its gin-and-bitters under pseudo-Venetian capitals…'

That sense of monstrousness abides in the Palace of Westminster. The German émigré W.G. Sebald would write of another gothic institution, the Palais de Justice in Brussels: 'At the most we gaze at it in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.'7 So too we see Westminster through a utopian/dystopian lens, an international emblem of all England, always seen in silhouette at one remove: from the river bank, from the train, or from the air. It seemed thus to Henry Mayhew and John Binny when they ascended over London in 1852. Republished in Humphrey Jennings' Pandaemonium, along with a Dore-like engraving of a ghostly balloon, its tethers hanging like severed threads, hovering in the penumbral, storm-clouds over the stalagmite-like skyline of the Palace of Westminster - a dark mirage out of the past or some apocalyptic future - the now industrialised city was laid before these nineteenth-century aeronauts, their journey made other by the altitude, like a map being unrolled in slow motion (a view which the contemporary visitors may obtain in a flight from the London Eye, itself a kind of Jules Verne fantasy for the millenium).

As Mayhew and Binny rose, so 'the earth seemed to sink suddenly down', leaving 'the leviathan Metropolis, with a dense canopy of smoke hanging over it, and reminding one of the fog of vapour that is often seen steaming up from fields at early morning. It was impossible to tell where the monster city began or ended, for the buildings stretched not only to the horizon on either side, but far away into the distance, where owing to the coming shades of evening and the dense fumes from the million chimneys, the town seemed to blend into the sky, so that there was no distinguishing earth from heaven'.8

So too Westminster would be transformed in the national imagination, from Turner's fiery vision and Whistler's monochrome view, the twinkling landmark of the tower of Big Ben would loom out of the metropolitan fog in the opening scenes of the Disneyfied Mary Poppins and Peter Pan and into its twentieth-century hubris, lying like some landbound Titanic on the banks of the Thames. I'm thinking of a sepia postcard lying by my desk, of the Victory Parade of 1919: a photograph of wedge-shaped First World War tanks slouching across Westminister Bridge towards Parliament. Are they celebrating the end of Armageddon? Or are they augurs of a new class revolution, an English Soviet - just as the same tanks had been deployed in Glasgow's St George's Square during the war to quell urban unrest?

I'm also reminded of the Independent MP, Noel Pemberton-Billing, a Lothario, aviator, inventor and futurist who drove round London in a self-designed car which looked more like a torpedo, and who had a ledge of skin grafted onto his cheekbone by plastic surgery so as to keep his monocle in place. In 1918 Billing alleged that the reason why the Allies were losing the war was because the German Secret Service had a Black Book containing the names of 47,000 members of the British Establishment addicted to sexual perversion. These men and women - many of them presumably habituees of Westminster - were being blackmailed by the Huns and thus the British will to win was being sapped. At the same time proposing other notions of the enemy within - not least the German Jews of Whitechapel, whom he demanded should wear cloth badges to denote the alien status of these long-established asylum-seekers - Billing's proto-fascist presence in the House of Commons was a challenge to the government; so much so that the then prime minister, Lloyd George, engineered to have the rebel MP thrown out of the House.

It was a scene unprecedented within that hallowed chamber. When the Speaker announced that Billing was to be 'suspended from the service of the House', Billing refused to move. The sitting was suspended, and officers were summoned to remove him. The incident - which has its echo in the 1980s when Michael Hestletine seized the ceremonial mace and earned his nickname of 'Tarzan' - was described with glee by the Daily Mail: 'The Speaker left the House, with several Members following him. The mace was removed from the table. Four messengers in evening dress, and wearing their gold chains of office, came in from the Lobby and closed round Mr Billing, the Serjeant -at-Arms directing operations from behind. (He did not draw his sword.) Mr Billing struggled hard, but the odds were against him. Two attendants seized a leg each, and two an arm each, and with a desperate wrench they got the member out of his corner and carried him feet first through the door, while other members laughed and cheered.'

The spectacle was redolent of Alice in Wonderland. 'The last the House saw of Mr Billing, through the swinging doors, was a scene of kicking legs and a flop on the floor of the Lobby. Fortunately the flop was on thick coco-nut mat and not on the hard tiles. In his struggles Mr Billing had grasped the shirt-front of one of his bearers and disarranged his Court dress. He also kicked another on the wrist. Thereupon they dropped him.'9 But this farce had a darker side: Lloyd George was told that Billing 'was carried out shouting "intern the Aliens"', while Billing's supporters proclaimed 'the crass stupidity of the Government in suspending Pemberton Billing has brought us nearer revolution than all previous acts combined of our subsidised marionettes. You would do well to sound public opinion, not the opinion of the camouflaged German Jews, of the monocled, eunuch-voiced inefficients who mince or waddle from Whitehall to the Clubs… That the traitors know what to expect is seen by the fact that the Statue of King Charles in Whitehall is now a machine gun emplacement' - a vision be reflected in virtual histories of SS stormtroopers marching over Westminster Bridge and Cold War fantasies of Parliament as a site for invasion from above, from Professor Quatermass to Dr Who.10

* * *

David Moore speaks of his photographs of the Commons in the context of 'the intentions of the nineteenth-century explorer photographers, who were most often in the employ of the British state to survey the colonies, for a wide range of potentiality, from land campaigns to agricultural intentions, passage, etc'.11 It is apt, then, that just along the river lies a tunnel through which transported convicts were disgorged from another institution - the verminous Millbank prison whose site is now partly occupied by Tate Britain - en route for banishment to the colonies. These wide waters were the conduit for imperial conquest, for the export of the unwanted and the import of plunder. Down in the warehouses of the docklands wharves were piled high with elephant ivory and Asian opium, an imperial trade regulated and taxed from and for the tenants of the Palace of Westminster. And so this powerhouse would abide, a sense of enclosing patronage that marched in step with the industrial age. It is no coincidence that Westminster commenced construction around the same time of the Lunacy Act, which determined that every town in the land should have a place of asylum for its mentally-ill (indeed, Pugin's contractor, the builder George Myers, was also responsible for the massive asylum at Friern Barnet). Thus, as the same time as Pugin and Barry's edifice rose over central London, multiplying in cell-like division, so the vast Victorian lunatic asylums extended the philanthropy of democracy to the insane.

My own subsequent memories of Westminster are also rooted in a certain subversion. I was at college in London during the awakening of punk: my contact with Westminster then was a series of marches routed past its then still soot-blackened, pre-steam-cleaned façade, protesting on any number of issues, from the Anti-Nazi League to the bombing of Libiya, from the miners' strike to the poll tax. All the while the Victorian complex stood as an architectural rebuttal to our democratic right to protest; an unyielding wall against which the Class War warriors could wage their civilian strife, creating, in the process, their own anti-governmental architecture: the turf mohican on place on the head of the statue of Winston Churchill; the attempt to sow fields of marijuana in the square around it; and up Whitehall their desecration of the cenotaph's empty tomb with graffitti: these auguries of inner city anarchy which would be enacted for real in downtown Baghdad.

I remember attending a book launch given on the Commons Terrace a week after 9/11: security was at its height as my fellow guests - many of them pillars of the establishment themselves - spoke of the possibilities of a terrorist attack on the Mother of Parliaments, by air or by boat; the body politic incarnate now a defensive site. That night, as I was walked its endless corridors past committee rooms and chambers, it was hard not to invest each with their own dramatic narrative, inflected with secondhand memories of Airey Neave's assassination by the IRA in 1979 - his car blown up on car park ramp - to tales of rent boys being given midnight tours of the nation's debating rooms by their uxorious sugar daddies.

Yet within this overblown version of a suburban villa - expanded ad infiniteum in its repeating arches - the machinations of Great Britain still take place, convened in endless committees and dark decisions while listless Oxbridge graduates operate as MPs assistants and catering staff cook up a Gormenghast-like storm, lacking only Peake's Swelter to swing his butcher's axe. Even now, even with its changed 'family friendly' hours, Westminster is a tradition as engrained as the Victorian pollution which still gives its façade a carbonised chiarscuro. It is still one great Pall Mall club, its terraces colour-coded between Lord and Commons, a democracy-defying diachotomy which rumour renders a venue of venal lobbying, coursed with influence and lucre through the anterior veins of its corridors and connective tissue of its cell-like chambers - the private dining rooms with their even darker panelled walls; places in which intrigue might yet foment and plots hatch over a fine burgundy.

Faerie palace or demon's lair, the Commons polarises as an acute paradox: a place of the people yet ultimately exclusive. It may yet wither under the media spotlight, or even under the microscopic examination of David Moore's lens. Through its daily appearance on our TV news, the building fades into political wallpaper, its architecture a shorthand for political discourse, serious TV (one recent BBC political strand used an animated version of Westminster reconfigured as a prehistoric monster; that sense of monstrousness once more). We see it so often in bulletins and rain-soaked political vox pops and pieces-to-camera from Parliament Green that the Palace recedes into a kind of generic gothic bluescreen, as much a CGI effect as a real building. So much more powerful, then, the intrusion of David Moore's forensic images as they pathologise the textures of that interior, painted and polished, scuffed and scratched. These are charged spaces, still echoing with speeches, just as the universe still echoes with the sound of human history. The perorations of nearly two centuries hanging in the air here, just as Marconi believed he could hear the voices of the dead from his telegraph listening station - the drowning cries of long-dead seamen still reverberating in the ether.

And these are the ironies which we inherit. The building may represent the will of the people, but the logo of Westminster - the medieval portcullis - speaks of defence and barred ways, antipathetic to the notion of democratic access. This is where David Moore comes in. His photographs take us into those chambers and under the seats; into the grain, as it were, examining, disinterring, preparing a visual autopsy of democracy; in his own words, 'an act of insolence in a period of absolute decadence.'12 And here, under the Prime Minister's microphone, we find a lump of chewing gum. Which is where Peter and I came in.

©Philip Hoare. 2003

Notes:

- Richard Davenport-Hines Gothic: Four Hundred Years of Excess, Horror, Evil and Ruin, Fourth Estate, 1998, 223

- Ibid., 223-4

- Ibid., 224

- Camille, 9

- David Watkin English Architecture, Thames and Hudson, 1979, 160

- Davenport-Hines, 225

- W.G. Sebald Austerlitz, Hamish Hamilton, London 2001, 23-4

- Quoted Humphrey Jennings Pandaemonium, Andre Deutsch, London, 1985, 266

- Quoted Philip Hoare Wilde's Last Stand, Duckworth 1997, 196

- Ibid., 197

- David Moore to Philip Hoare, 16 January 2004

- Ibid.